The Creative Parent Paradox

And the problematic pram in the hallway

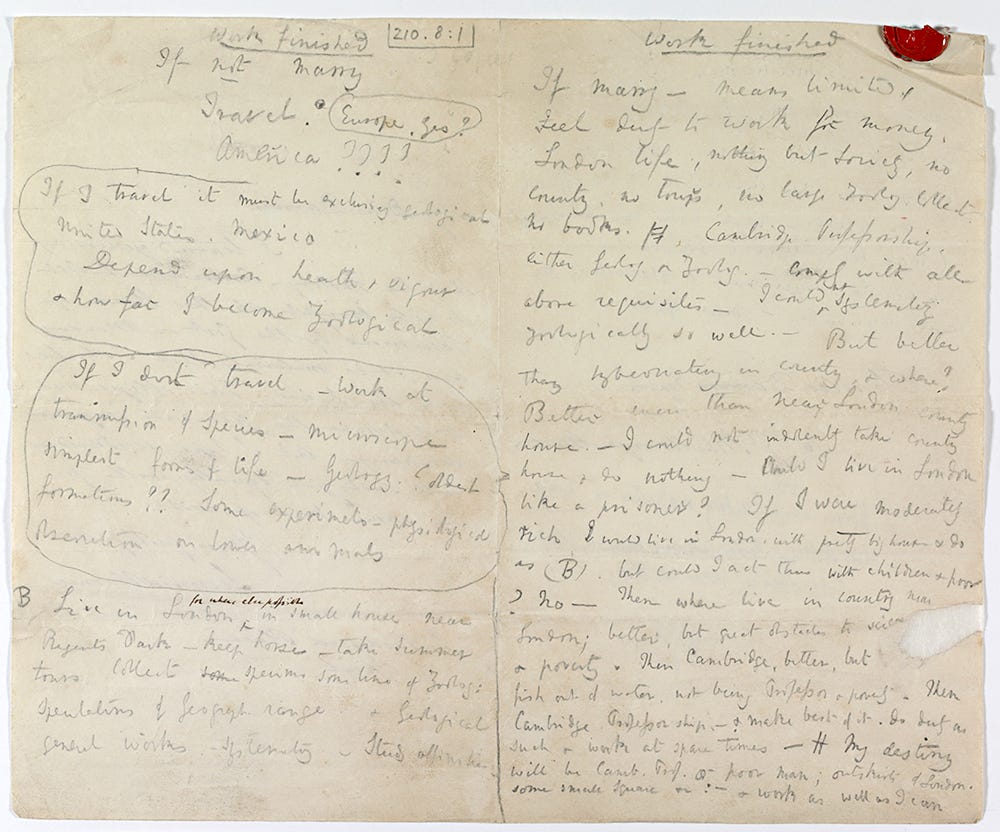

On April 7th, 1838, Charles Darwin opened his notebook to muse on marriage. He was considering taking Emma Wedgwood, his cousin, as his bride. (Don’t smirk—it was all the rage back then, putting him in a historical clique with men as renowned as Albert Einstein, Edgar Allan Poe and Jesse James.)

He wondered whether his life would be better spent alone or alongside his wife-to-be. One of history’s greatest thinkers attempted to answer this unquantifiable question using—you guessed it—a pros and cons list.

Darwin could clearly see positives to a life shared with a loving companion:

It is intolerable to think of spending one’s whole life like a neuter bee, working, working, & nothing after all. Imagine living all one’s day solitarily in smoky dirty London House. Only picture yourself a nice soft wife on a sofa with good fire, & books & music perhaps.

But to settle down was to give up a life filled with:

— Freedom to go where one liked — Conversation of clever men at clubs — Not forced to visit relatives & to bend in every trifle. — Perhaps quarrelling — Loss of time. — Cannot read in the Evenings — Fatness & idleness — Anxiety & responsibility — Less money for books

Less money for books. Heaven forbid. (Sidenote: has anyone turned Darwin’s list into a PowerPoint? I’d love to see it.)

Francis Bacon1 came down harder on the institution in his essay "Of Marriage and Single Life," suggesting only the unmarried can achieve greatness:

He that hath wife and children hath given hostages to fortune; for they are impediments to great enterprises, either of virtue or mischief. Certainly, the best works, and of greatest merit for the public, have proceeded from the unmarried or childless men, which, both in affection and means have married and endowed the public.

Writer and critic Cyril Connolly agreed, suggesting: “There is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hall.” Back in 2005, Lionel Shriver, author of We Need to Talk About Kevin (not this Kevin, thankfully), wrote a manifesto for the anti-mom titled “No Kids Please, We’re Selfish,” sharing her belief that “my life is far too interesting to spoil it with children.” Allison P. Davis took that torch earlier this week, wondering, “Why Can’t Our Friendship Survive Your Baby?” This essay came from the perspective of someone “left behind” after all her interesting friends had become “conventional and heteronormie” and … well. It's best you read it for yourself. No lies are found in Today in Tabs’ take that “the real delight of the piece is the slow-burn self-revelation that Davis’s struggle to maintain friendships with the parents in her life is mostly because she’s kind of awful to them.”

Maybe the answer isn’t to avoid parenthood entirely but to limit the amount of children you have. Lauren Sandler argued her case a decade ago, suggesting that there was a secret to being a successful parent and writer: “Have Just One Kid.”

Childless at 48, I'm now old enough for the question of motherhood to have become merely philosophical. Still, I've had all the time in the world to have babies. I am married. I've been in perfect reproductive health. I could have afforded children, financially. I just didn't want them. They are untidy; they would have messed up my flat. In the main, they are ungrateful. They would have siphoned too much time away from the writing of my precious books.

Please be upstanding for Zadie Smith, who clapped back in the comments:

I have two children. Dickens had 10—I think Tolstoy did, too. Did anyone for one moment worry that those men were becoming too fatherish to be writeresque? Does the fact that Heidi Julavits, Nikita Lalwani, Nicole Krauss, Jhumpa Lahiri, Vendela Vida, Curtis Sittenfeld, Marilynne Robinson, Toni Morrison and so on and so forth (I could really go on all day with that list) have multiple children make them lesser writers? Are four children a problem for the writer Michael Chabon—or just for his wife, the writer Ayelet Waldman?

We need decent public daycare services, partners who do their share, affordable childcare and/or a supportive community of friends and family. As for the issue of singles v multiples v none at all, each to their own! But as the parent of multiples I can assure Ms Sandler that two kids entertaining each other in one room gives their mother in another room a surprising amount of free time she would not have otherwise.

We live in a society where having children is no longer the default path, and many choose to take the road less arduous. The language we use around this route is fraught with sensitivities—is this person “child-free”, having made a conscious decision not to have children? Or are they “childless,” their agency taken from them, wanting more than anything to become parents but with insurmountable barriers—physical, mental, societal or financial—standing in their way?

With so many deciding—or accepting—a life without children, while parents experience the sheer exhaustion that family life brings, it’s only fair to wonder if Cyril Connoly was on to something and the pram in the hall could be as a tombstone marking the death of creativity in a household. Once a child enters your life, are they in competition for the time and energy of your creative endeavours? Might we have more in the tank to give without the constant depletion that raising kids entails?

I can’t offer an unbiased opinion—not with this much skin in the game. My decision to marry, and our decision to have children, brought me to where I presently stand: a life I’m grateful for every day, even on the toughest of them. Without my son, and my experience with paternal post-natal depression after his birth, I may have never turned my hand to writing—let alone be closing in on three years of this newsletter. My second child put me through the wringer in a way that fundamentally transformed how I see the world and the space I choose to inhabit in it. Religious texts, spiritual practices and mindfulness exercises all espouse a similar belief: if you can see the difficult experiences in your life as ones that grant you experience, help you grow, and strengthen your resolve, then even the most challenging situation is an opportunity for growth. What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. Roll your eyes if you must, but there’s a reason that Nietzsche’s proverb has stayed strong for almost 150 years and will continue long after we depart this mortal coil.

On the aforementioned Michael Chabon: he once shared a piece of advice from a writer he admired: “Don't have children. That’s it. Do not. That is the whole of the law. You can write great books or you can have kids. It's up to you.” Chabon railed against the advice; a decision he doesn’t regret:

If I had followed the great man's advice and never burdened myself with the gift of my children, or if I had never written any novels at all, in the long run the result would have been the same as the result will be for me here, having made the choice I made: I will die; and the world in its violence and serenity will roll on, through the endless indifference of space, and it will take only 100 of its circuits around the sun to turn the six of us, who loved each other, to dust, and consign to oblivion all but a scant few of the thousands upon thousands of novels and short stories written and published during our lifetimes. If none of my books turns out to be among that bright remnant because I allowed my children to steal my time, narrow my compass, and curtail my freedom, I'm all right with that. Once they're written, my books, unlike my children, hold no wonder for me; no mystery resides in them. Unlike my children, my books are cruelly unforgiving of my weaknesses, failings, and flaws of character. Most of all, my books, unlike my children, do not love me back.

Chabon later wrote The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, which I’d argue should remain “among that bright remnant” that will outlast us all. He also found inspiration—and unbridled joy—in the lives of his children, taking his teenage son to Paris Fashion Week to meet Virgil Abloh. This was beautifully captured in another essay for GQ: “My Son, the Prince of Fashion.” (There are a few pieces of writing I’d put in my fatherhood hall of fame. This is one of them.)

Austin Kleon suggested, “Rather than being ‘the enemy of art’ your children can inspire you to go new places. Hanging around a four-year-old can get you unstuck.” Karl Ove Knausgård’s escapades as a full-time father were spread across six books, totalling thirty-six hundred pages, provocatively titled “My Struggle.”2 For Knausgård, fatherhood delivered an exothermic reaction to his creative output rather than draining its vitality away. His first two books had been moderately successful; his writing on the minutiae of fatherhood turned him into a global sensation. His experience on the coal face of parenting proved transformative, with observations on being the primary carer becoming the ne plus ultra of dad-lit; his detailed explanations of the mundanity of parenthood continue to inspire readers across the world to seek out the extraordinary beauty of life’s most ordinary moments.

Becoming a father is hard. I don’t think I’ll ever take on a more challenging job. A fundamental part of my own growth, understanding what is necessary in my role as a father, and what I need from those around me, is to be continually reminded of the importance of learning to to let go. Because for everything that pram in the hall takes from us, what it gives, beyond all else, is a role to play—a sense of purpose in becoming something for these children you have sired, providing them with what you may have found lacking in your old childhood, and breaking the cycles of those who came before you. If that inspires you to do something bigger, so be it. But it isn’t necessary. Leaving you in the capable hands of Knausgård:

“I am alive, I have my own children, and with them I have tried to achieve only one aim: that they shouldn’t be afraid of their father.

They aren’t. I know that.

When I enter a room, they don’t cringe, they don't look down at the floor, they don’t dart off as soon as they glimpse an opportunity. No, if they look at me, it is not a look of indifference, and if there is anyone I am happy to be ignored, it is them. If there is anyone I am happy to be taken for granted by, it is them. And should they have completely forgotten I was there when they turn forty themselves, I will thank them and take a bow and accept the bouquets.”

3 things to read this week

A whole load of links up there are well worth your time, but these three are getting a rewind so you don’t miss out. Some big hitters here this week. Enjoy.

“What Is the Struggle in ‘My Struggle’?” by Joshua Rothman in The New Yorker.

”Knausgaard’s book is […] about more than the experience of a son. That’s because, in exploring that experience, Knausgaard has ended up exploring all experience. If being a writer is like being a swimmer, and life is like the ocean through which you swim, then Knausgaard’s book starts out being about the waves but ends up being about the stroke. His father’s anger is one of those waves, and Knausgaard, early on, learned to see the wave coming, to brace himself, to swim up its face and, hopefully, to dive beneath before it swept him up.”“My Son, the Prince of Fashion” by Michael Chabon in GQ.

”When he started kindergarten, however, [my son] found that the wearing of costumes to school was not merely discouraged, or permitted only on special days, as in preschool: It was forbidden. It would also, undoubtedly, have incurred an intolerable amount of mockery. Abe's response was to devise, instinctively and privately, what amounted to a kind of secret costume that would fall just within the bounds of “ordinary attire” and school policy. Over the next few years, with increasing frequency, he went to school dressed up as a man—a stylish man.”“The Pram in the Hall” by Shane Jones in The Paris Review.3

”There is some light on this topic. I’ve discovered many writer-fathers who not only continued to produce work, but produced work that is richer and more interesting because of their fatherhood. William Vollmann has a daughter. He rarely mentions her in interviews, and I can’t recall a single instance where she appears explicitly in his writing, but Vollmann once told an interviewer that having a child was the most fulfilling part of his life; he enjoys having her in his studio as he works. Vollmann has always been prolific, but arguably his best work, the National Book Award–winning Europe Central, was written while his daughter was a small child. J. M. Coetzee, Thomas Pynchon, Ben Marcus, Rick Moody, Martin Amis, Richard Brautigan, and Vladimir Nabokov are all fathers who created powerful work after having children. For the right man—and for plenty of men—the pram in the hall has the opposite effect of Connolly’s: it’s a motivator.”

One for the white noise crew

We got talking about white noise4 in the community this week and two solid tips came out of the conversation. One is that the Yogasleep Hushh machine is money well-spent. Second, if you’re stuck and need something to do the trick, your iPhone has a built-in white noise function in accessibility settings.

Now go the fuck to sleep, little one.

Hey! Listen to this!

Did you catch the Turtles movie yet? Go see it—it’s like giving your eight-year-old self the gift of a lifetime. It’s still on in some theatres or available to buy on Amazon. It’ll surely hit one of the streaming services soon—hopefully one you’re paying for?

The soundtrack is one of this year’s best, a beautiful throwback to the hip-hop sounds of 90s New York, with some Liquid Liquid and ESG thrown in for good measure. COWABUNGA!

Good Dadvice

Say Hello

That’s it for this week. As always, tell me how it was for you.

Loved | Great | OK | Meh | Bad

Branding by Selman Design. Illustration by Tony Johnson. Survey by Sprig.

I can never read the name Francis Bacon without thinking of this piece of Reddit history.

If you’re wondering why someone would name their book after Hitler, then the New Yorker has you covered with 2014’s ”Why Name Your Book After Hitler?”

I am also unable to read anything about The Paris Review without thinking of this tweet. “And now, little man, I give the watch to you.”

We also talked a little about brown noise as one dad had tickets for Sunn O))). We’ll leave that conversation in the app.

"Cannot read in the Evenings?" Who says? Why, I have enjoyed many happy hours since the birth of our child reading such marvelous literary creations such as "Green Eggs and Ham", "There's a Wocket in my Pocket", and "One Fish Two Fish", not to mention other tales about scaredy squirrels and peek-a-boo farms and whatnot.

I wouldn't be writing here on Substack were it not for having my daughter