In Memory of Mary Maguire

Beloved Wife, Mum & Nanny. November 15, 1961 — May 30th, 2024

The last time I was in your inbox I wrote about finding strength in Pema Chödrön’s book When Things Fall Apart. What I didn’t share with you was the reason I had turned, once again, to that book.

Three weeks ago, my mother received a terminal cancer diagnosis. We were told she didn’t have long. I grabbed my copy of the book, stuffed some black clothes into a bag, and jumped on the next plane to Manchester. I read it to myself 30,000ft above the English Channel. We read it together by her bedside, my dad listening intently. I looked through her Goodreads and ordered two of her all-time favourites to be delivered to the house—Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Once Upon A Time in Cholera and Bill Bryon’s A Walk in the Woods—so I could read them to her.

I clearly expected more time together.

Minutes before she left us, a priest arrived at the house. This was the third in as many days, another man of the cloth who considered Mum a close friend. You can’t expect to have been crowned Catholic Woman of the Year 2013 and not pick up some clergy superfans along the way.

She was in a hospital bed but comfortable inside her own house, with a direct view into the garden she adored. Father Jim sat by her side and began to pray. My sister—an NHS nurse who has dedicated her life to helping people at the end of theirs—knew my mum would soon breathe her last breath. Father Jim began to sing, “The Lord is my Shepherd.” Halfway through, at these words, Mum left us:

For Your endless mercy follows me

Your goodness will lead me home

And though I walk the darkest path

I will not fear the evil one

For You are with me, and Your rod and staff

Are the comfort I need to know

And I will trust in You alone

Father Jim said that in 30 years of service he’d never seen such a beautiful passing.

We buried Mum on Monday. It’s all still very raw. I wasn’t sure I’d write anything this week, but as you’ll see, “Mum made me do it.” She dedicated the last 15 years of her life to helping Kenyan orphans living in poverty. She founded and ran The Good Life Orphanage with my dad. It all started after a family holiday in Mombasa as a teenager; I’ve been involved with the rest of the family since the start, but that’s a story for another time.

I didn’t write anything here last week. I wrote other things: emails to funeral directors and priests, a mass text message to be sent to friends and family, a final post for Mum’s Facebook page informing friends and family about funeral logistics.

I wrote a few things for myself. It was all a blur; I needed to know I’d have memories to return to, an aid in recalling chunks that already feel like they’re slipping away, a record of strange coincidences that amount to nothing on their own but become more than the sum of their parts when viewed as a whole.

On the morning Mum died, my sister walked into the room wearing a hoodie that said Find art in everything. “That’s an interesting choice for today,” I suggested. “I just grabbed it from Mum’s cupboard,” she replied. “All my clothes are dirty. I didn’t see what it said.”

Small things that, on a normal day, I’d have paid no mind. I’d never seen my mum wear it once. If I would have? I’d have rolled my eyes and thought it was exactly the sort of “live, laugh, love” thing she always went for.

Death has an unparalleled ability to imbue the insignificant with new significance.

A Eulogy for Mum

Delivered on June 3rd, 2024

Mark Twain once wrote, “If I’d have had more time, I would have written a shorter letter.” Mum passed away four days ago, so I hope you’ll forgive the length of this eulogy.

I can’t remember a lot about my grandad’s funeral. I was only 7. But one thing that stuck with me was how strange it could be that a life so big could be contained in a box so small. I’ve thought about that at every funeral since. Now, as I stand here today saying goodbye to Mum, I am sure I’ll never be at a funeral where the size of the life and the impact that person had will be so at odds with the size of the coffin.

Mum was a small woman, but what she may have lacked in physical stature, she made up for with strength, courage, kindness, and sheer force of will. She was many things to many people, but to us, she was mum, nanny, or simply “Mure.”

Mum was born in Badoney, Country Tyrone, on what I assume was a cold and wet November morning. My sister already told you how my Mum and Dad met. A few years later, sometime in 1978, they moved over to Scotland. They lived in a caravan for the first few years of their relationship, saving up the money to pay for a wedding and a deposit on a house. Mum got a job working at a tea factory, stuffing bags into boxes, and she’d come home at the end of the day, steep herself in the bath, and watch the water slowly transform through different shades of brown. They moved down to Manchester a few years later—she was working as a shop assistant at Topman while pregnant, a fact that delighted me as I grew older. It still makes me smile to imagine my mum sauntering around the shop floor in 1982 with huge shoulder pads, bopping along to Soft Cell’s “Tainted Love.”

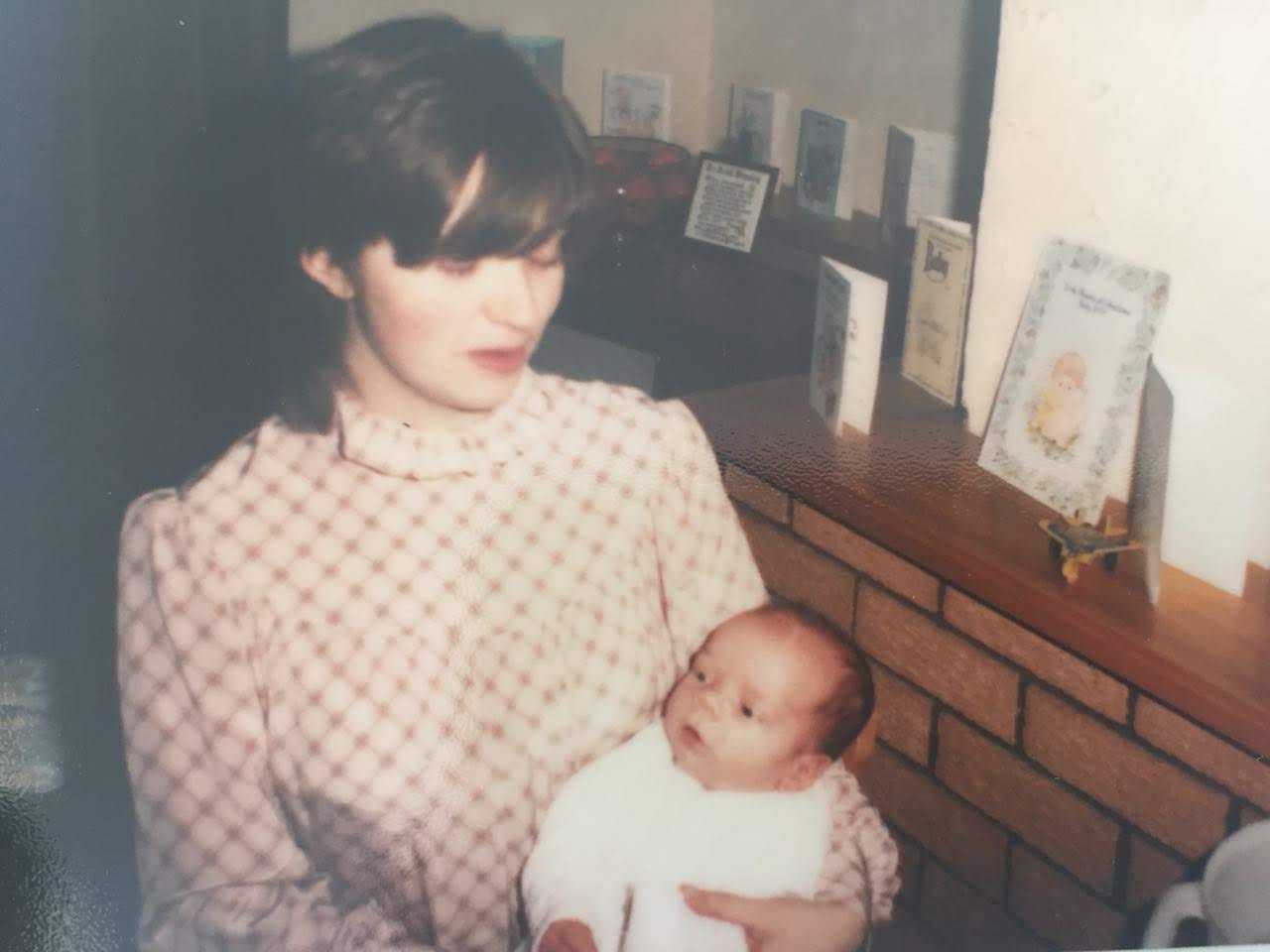

I was born. The twins followed soon after. Dad worked away during these early years, following jobs wherever they went. All roads may lead to Rome, but back then most roads lead away from Manchester. He’d be away for as long as six weeks at a time, picking up weekend shifts that paid time and a half. Mum would stay home, raising three kids on her own, with friends and family providing much-needed support. Back then, a father’s job was as simple as bringing home an envelope of cash at the end of the week, and that’s what Dad did. It wasn’t until I had small children of my own that I realised how much harder Mum’s job was.

When she’d survived those early years and got us off to school, she went back to work, following dad into the world of “civils,” or, to those less familiar with the lingo, “digging holes.” Our childhood was defined by various eras of three-letter acronyms—OBG, NTG, EOM—as holes were dug across England as part of what we still lovingly call “the Irish construction mafia.” After a while, they added an acronym of their own: MCE, or Maguire Civil Engineering. Theirs was a brilliant partnership: Dad was the brawn, Mum was the brains. Dad may have been more visible, making his presence known by banging desks and launching phones and furniture, but we all knew it was Mary—working diligently and without fanfare behind the scenes—who kept the trains running on time.

In a house that was never short on F words, Mum’s last weeks were defined by three: her friends, her family, and her faith. All three of these gave her strength throughout her life and helped carry her through until her last breath. People always talk about cancer in aggressive terms: a battle to be fought, an opponent to be defeated. Mum faced the worst possible news with courage and dignity that I can only wish to embody when my time is up. Her last two weeks were short, but she did not lose. She was not afraid. Not one little bit. She would go out on her terms. She did not grasp at vague illusions of hope, flailing to hold onto potential life rafts that might have given her a little more time but would have kept her away from her family, her home, and the garden she loved to potter around in.

She stared death down. She did not flinch. My uncle Gerald told us, “Of course she isn’t afraid. After all she’s done, if she’s not getting in upstairs, what chance do the rest of us have?” Father Gabriel said if he got up to the pearly gates and Mary wasn’t already there waiting for him, he wouldn’t go in himself.

The outpouring of grief and sympathy we’ve seen over the last few days has been a powerful reminder—if we’d ever need it—of Mum’s unequalled ability to alter the trajectory of the lives that came into her orbit. I’ve heard stories from her friends over the last few days about her selflessness, how she lifted up and championed those around her and made the impossible seem entirely achievable.

So many of you have told us, “We were privileged to know her.” We feel exactly the same.

You will be nodding, thinking about how she altered the trajectory of your life. When we all gather later for a drink—and I do mean all of us—I look forward to hearing your stories too. When I look at where I am today, so much of what I hold dear was given to me by her—a lifelong love of words, an unhealthy obsession with music, a proficiency with technology. She bought me my first PC and was patient enough to let me commandeer the phone line as I adventured into the early internet. She took me to my first gig to watch The Pogues in the Apollo, where I fell asleep halfway through. She dropped me back outside the same venue a decade later, sometime around 5 am, so I could queue up for Oasis tickets, staying parked in her car around the corner. We constantly traded our favourite books and TV shows; I learned over the last week that this was a pastime she shared with many of you. She gave me so much, but more than anything else, she gave me belief. She believed in me and allowed me to believe in myself.

She believed in my dad, too. Right from the start. You’ve never seen a woman so devoted to her husband. She followed him out of Ireland, to Scotland, to Manchester, and eventually to Kenya. Whatever hair-brained scheme Dad might have had, she leapt into it with all her heart. One of my biggest revelations over the last two weeks was seeing how deeply my parents loved one another. The love she had for my dad was eventually matched by the love she felt for her grandchildren. She adored them. They lit up her world, and she had a unique relationship with each one—her empathy shone through as she connected with each exactly as a nanny should. I know they will all miss her as much as we do.

To steal a line from Bluey, a show she loved to watch whilst cuddled up with grandkids on the sofa, “She was about the nicest nanny you would ever want to meet.” We all knew that. But it was her work with The Good Life Orphanage (or the GLO, another three-letter acronym) that will have led many of you to a similar conclusion. It was a family trip to Mombasa in our early teens that would define the final chapter of Mary’s life.1 My parents returned from a holiday and were so moved by the people and the poverty they wanted to do something to help. They didn’t speak Swahili, they didn’t know how local laws and bureaucracy worked, they had no idea how to run a charity in one country, let alone two. But they did it. I always thought they were out of their mind to undertake such a project. I learned in the last few days that Mum and Dad often said the same thing to each other. But that was Mum in a nutshell: just like the Gospel reading that she chose today, she was unable to witness the pain of others and walk on by. She dedicated the final chapter of her life to helping those who weren’t born into the same privilege most of us here have been. As her friend Anne-Marie said to us this week, “She made us all better people by opening our eyes to the suffering of others.”

After my daughter was born I called my mum to share the news. Through tears I told her, “I can’t believe you did that for me.” I still can’t. Mum’s life was one of sacrifice. She gave everything she had for others. For her husband, children and grandchildren. For the hundreds of kids who came through the gates of The Good Life Orphanage, finding love and warmth in one of the many family houses: Kilroe, O’Malley, McKenna, Flynn and Maguire. The hundreds more kids who enrolled at St Bernadette Mary School to find a way out of poverty through education. The disabled children who came to Hattie’s House and received occupational therapy after years of living with untreated ailments. And that’s without getting into all the staff, extended families, and community members gathered into her loving embrace.

Two nights before Mum left us, my sister Sinead had allocated some time for life logistics: bank PINs, email passwords, orphanage accounting. When the time arrived Ruby and Niamh, her eldest two grandchildren, came into the room and sat at the bottom of her bed, just hanging out. Mum asked for some of her favourite songs, and the girls played them through their phones: The Waterboys, The Beautiful South, Hothouse Flowers, R.E.M. Mum had just recently returned from Barcelona with the two of them and asked: “Let's play the Beyonce song from our trip.” Startling my sisters, Mum belted out a perfect rendition of “Texas Hold 'Em” and even had the hand gestures to accompany it. It was a beautiful moment and the epitome of time well spent. But if anyone does have the six-digit code to log into her online banking, please come and grab me at the end of the service.

As difficult as the last few days have been, we have found moments like these to laugh and smile, bittersweet memories amidst unbearable pain. Mum woke to the news that her beloved Manchester United had won the FA Cup, preventing our noisy neighbours from their historic double-double. As we chose readings for this mass, I sat by her bedside and read passages of the Bible that I had shortlisted for the funeral, which brought a huge smile to her face, a glimmer of hope that the prodigal son she spoke of so often might be returning to the flock. My sisters nursed her in her last days—their final gift—and my dad and I would hear the three of them giggling as Claire taught Sinead the ropes in a real baptism of fire. She witnessed her family come together and unite in love, holding space for a tender, heartfelt goodbye. And, of course, you can only imagine the smile on her face as she saw a Prime Minister that none of us voted for standing in the pouring rain and finally agreeing to release us from 14 years of collective torture. (This is your reminder—you can all do Mary one last solid and head to the polls on July 4th. We all know what she would have wanted.)

In society, we talk a lot about what it means to live well. Few spend their lives as well as Mum. But not only did she live a good life, she died a great death, something I really have to thank my sisters for. A belief in the Hindu religion is that those who pass peacefully and without suffering have spent their lives building up karma by doing good deeds here on Earth. Mary spent her last days at home surrounded by her family: her husband who prayed with her over her bedside; her children—the three she gave birth to and their partners who were so dear to her; her brothers and sister who lit up her last days; and those final memories with the grandchildren she so adored.

So many of you have spent the last few weeks asking questions: the whys, whens, and hows that led to her being taken from us too soon. But today is not a day for these. Today is the day we celebrate Mary's life, the lives she touched, and the lessons we might learn.

Today, and every day henceforth, we should ask ourselves: “How can we Be More Mary?” How can we carry her in our hearts and take her strength to help us navigate our moments of struggle? How can we embody her patience, determination and grace? How can we be better people, putting others' needs ahead of our own? How can we look out for each other: not just those who have, but those who have not? How can we forgive and forget? How can we learn to love and let go?

It’s a tall order. Mum made it look so easy. It won’t be, especially not without her. But as we leave here today, we can take a little bit of her light and love with us and spread it far and wide; every day, in every way, we might ask ourselves how we could Be More Mary.

Mum wanted everyone to come today dressed in their brightest colours. She didn’t want this to be a sombre affair, a sad full stop to an unforgettable story. In honour of her, I offer up these words from the poem “Funeral” by Rupi Kaur.

when i go from this place

dress the porch with garlands

as you would for a wedding my dear

pull the people from their homes

and dance in the streets

when death arrives

like a bride at the aisle

send me off in my brightest clothing

serve ice cream with rose petals to our guests

there's no reason to cry my dear

i have waited my whole life

for such beauty to take

my breath away

when i go let it be a celebration

for i have been here

i have lived

i have won at this game called life

Mum had two final wishes for her funeral: that all attendees wear their brightest colours and that, instead of flowers, attendees would consider making a donation to the orphanage in her name.

I might not keep regular office hours here over the next few weeks. Then again, I might. Writing helps. I’ll give myself the same advice I’ve been giving my dad for the last few weeks: take it one day at a time.

If you’d like to hear more about the orphanage's origin story, you can watch my mum being interviewed on Irish TV here.

Just perfect x

I'm so sorry for the loss of your Mum Kevin, I recall this poem as I think of you both...

‘When all the others were away at Mass’

When all the others were away at Mass

I was all hers as we peeled potatoes.

They broke the silence, let fall one by one

Like solder weeping off the soldering iron:

Cold comforts set between us, things to share

Gleaming in a bucket of clean water.

And again let fall. Little pleasant splashes

From each other’s work would bring us to our

senses.

So while the parish priest at her bedside

Went hammer and tongs at the prayers for the dying

And some were responding and some were crying

I remembered her head bent towards my head,

Her breath in mine, our fluent dipping knives -

Never closer the whole rest of our lives.

by Seamus Heaney