Why I wish people would ignore my child

Being ignored is a privilege I now realise I've always taken for granted.

The New Fatherhood explores the existential questions facing modern fathers, bringing together the diverse community of forward-thinking dads who are asking them. Here's a bit more information if you're new here. My aim is to make this one of the best emails that you get each week. You are one of the 1,920 dads (and curious mums) who have already signed up. If you've been forwarded this by someone else, get your own one here.

One of the key things that I’ve said about The New Fatherhood from the start is that this isn't about me, it's about all of us. So I'm always looking to share perspectives on fatherhood that communicate the multitude of feelings we’re facing. So that's why I'm handing the reins over to Stuart Waterman today. Stuart is a Content Strategist / Copywriter tentatively re-entering the world after two years as a full-time dad. You can follow him on Twitter or, er, link in with him on LinkedIn.

I’m currently really enjoying the audiobook of Limmy’s autobiography. In one chapter he describes what it’s like to suddenly become famous; the feeling of having strangers looking at you, taking surreptitious pictures of you, staring at you as you eat a packet of crisps on a train.

It struck a chord with me, because that feeling of awkwardness and discomfort is not dissimilar to what I sometimes feel when I take my son to the park, the playground, or indeed anywhere else in public.

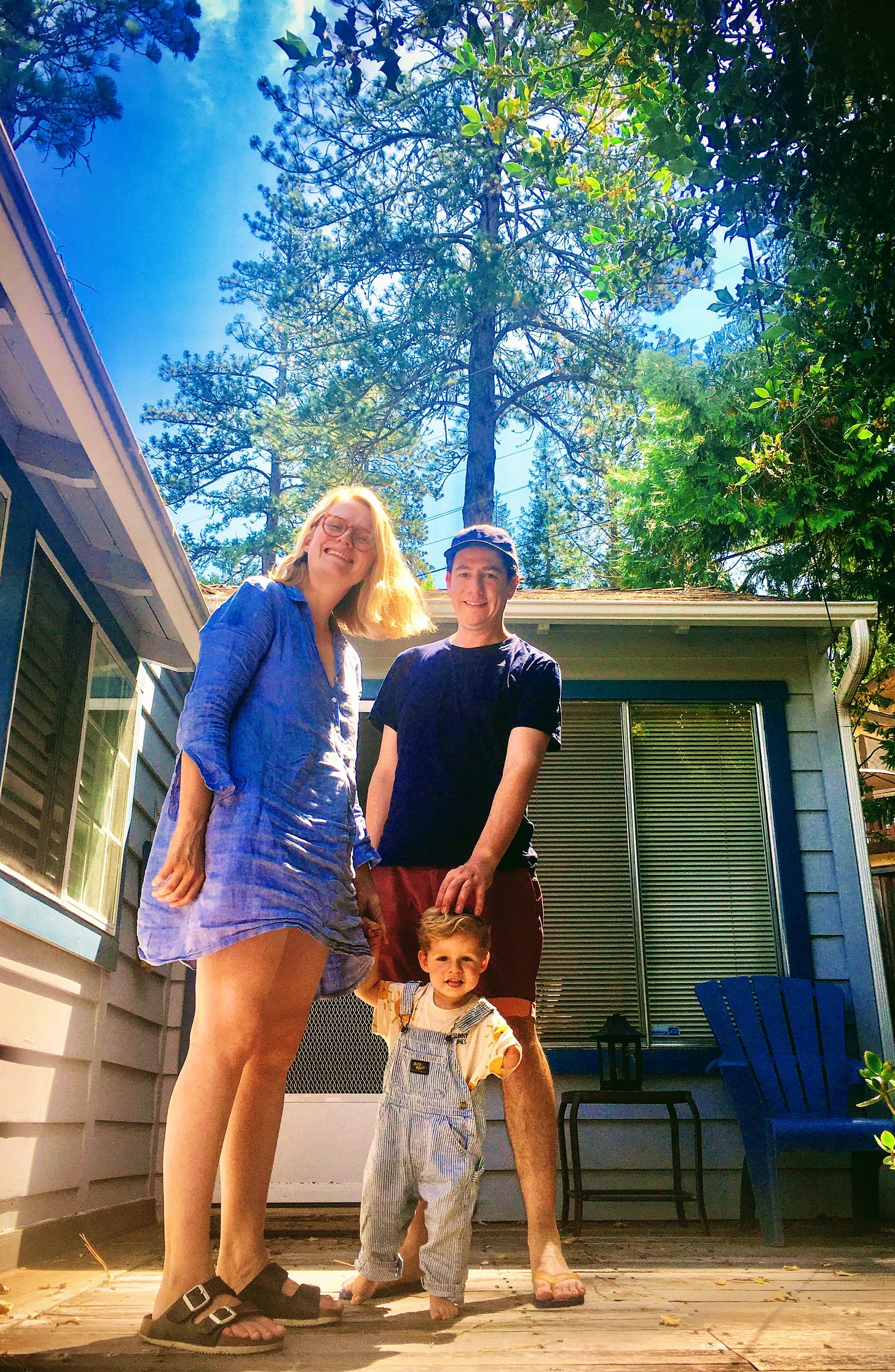

My son, who is two and a half as I write this, was born with no forearm or hand on his left side. We learned this at the 20-week scan, so in theory we had plenty of time to get used to the fact. But however inevitable some of the challenges we’re coming to face have always felt, it somehow doesn’t make them any easier.

I’m not talking about challenges around stuff like getting dressed, using cutlery, carrying things, etc. He has, and will continue to find ways that work, with or without prosthetic assistance, and occupational therapy and the like can help. I mean the challenges around dealing with other people, and their reactions to him.

I’m an introvert, and always have been. I’ve successfully worked on the muscle that enables me to step out of that profile when I need to, as work and social occasions require. But there’s something about having strangers stare at my child that sometimes makes me want to run home, close the door and lock out the world.

Don’t get me wrong, the interest he receives is not always unpleasant. Kids especially, below the age of, say, six, are often inquisitive, kind and friendly. They ask questions from a place of genuine curiosity which, in the voice of an adult, might feel uncomfortable: “What happened to your baby’s arm? Was his mummy upset when he was born? How does he clap? Can he climb?”

The hard part for an introvert like me is when I just want to spend an hour playing with my kid and not have to talk to anyone, let alone find delicate ways of answering well-meaning questions from little ones. My wife and I have a set of considerate answers we trot out, but it’s hard to prepare for unpredictable follow-up questions and comments, and even more challenging when our son (thus far definitely not an introvert) is trying to sprint behind an occupied swing that’s about to wallop him. It’s not the easiest time for a sit-down chat about how we’re all born different, you know?

That’s before we consider the less kind looks, questions and comments that can arise. We’ve actually been relatively ‘lucky’ in that sense so far. In one Facebook group we’re members of, a mum recently told a story about how a passing adult had referred to her son - around our little one’s age - as ‘a freak’. How are you supposed to respond to that?

Now, we don’t spend all our waking hours worrying about this stuff. It generally doesn’t limit what we do with our child. Most days, we can go about our business without it being a consideration. But on a bad day I can find myself gazing enviously at kids and parents who get to just run around, hang out with friends, talk to who they want to, and not have to feel that lurch in the stomach that comes with feeling observed.

Honestly, I’ve sometimes left his big coat on for longer than the other kids, because his limb difference (that’s the PC term, folks) is less visible in bulky clothing. But that becomes less feasible as the weather gets warmer. I’ve swerved to avoid a particular playground if I see a certain older child is playing there, because the week before they made an unkind comment. But as our son starts to express preferences and opinions about where we go and what we do, that too becomes harder to do.

Basically, the opportunities to consciously avoid situations that lead to me feeling a sudden, alarming, protective rage are lessening.

Ah yes, the rage. I’m not angry at whatever unfairness we may feel/have felt that led to our son’s disability. I think I’m angry at the sheer monotony of having to address it, refer to it, acknowledge it, over and over. I suppose I’m angry that he won’t get to go unnoticed.

Is the rage a peculiarly male thing? Definitely not. But the fear that it may turn into physical action which could get me into actual, life-altering trouble is probably more likely to be felt by me than my wife.

I don’t have a history of violence, nor any intention to acquire one. I didn’t grow up in a violent household. But I did grow up around stories in which violence was, sometimes, framed as the right answer. The answer to the question: “What do you do if you need to protect yourself or your loved ones?”

Add to that the obvious: I’ve never been a parent before, and therefore I’ve never had a child with a disability before, and therefore I’ve never had to develop whatever associated coping mechanisms are required. I’m a straight white male who looks just like all the other straight white males - I’ve frankly been able to coast through life without drawing much unwanted attention. The feeling of being ignored is a privilege I now appreciate I’ve always taken for granted. That realisation, at least, feels useful (if belated).

But I worry about the rage because however uncomfortable the attention can be at times, really, this period right now is the easy bit. Our boy goes to a nursery he loves, he’s making friends with kids and adults who accept him for who he is, and he hasn’t yet developed any self-consciousness around his particular difference.

But what about when he goes to ‘big’ school? When he becomes a teenager? When he enters the world of work? We all dread the thought that our child might be bullied. What are the prospects for a child who looks uniquely, conspicuously different?

It was this line of thinking that really got to me when we first heard the news about his condition. The thought that he - we- will need to develop the tools and strategies to cope with how the wider world reacts to him was (and sometimes still is) overwhelming. The thought that our beautiful, happy little boy might have his (currently very loud) spirit dampened by unkindness creates in me a kind of heartbreak I’ve never experienced before.

Throughout the pregnancy and his life so far we’ve always said we’re not going to hide away what makes our son look different. And being part of communities like Reach (for children with upper limb differences) has shown us that, practically speaking, our boy will grow up to forge his own way in life, and there will be nothing he can’t do.

I suppose my wife and I just need to reconcile ourselves to the fact that, as he goes about getting on with it, we need to keep working on how we react to others’ reactions. Because that's the model for how he himself will react.

3 things to read this week

One interesting thing about being part of a community of difference is that there is no one way to think about helping your child develop. Some doctors propose prosthetics early to help children get used to them; whereas many parents feel it's more important to help their child get used to their body as it actually is. One thing most tend to agree on—whether they have a limb difference or not—is that Open Bionics' Hero Arms look amazing. I mean, what kid doesn't want to look like something out of Star Wars or Iron Man?

#ProjectLimitless is an inspiring initiative that aims to provide a functional prosthetic to every child who needs one. This has led to innovative approaches in building and funding new kinds of prosthetics, and has seen the founder of UK social impact company Koalaa being included in Forbes' 30 under 30 list.

Completely unrelated but pops into my head anytime someone asks me about good stuff to read: this New Yorker article from 2012, about a rather odd dentist, is one of my favourite 'longreads' ever.

— Stuart

Say Hello

That's it for this week. Thank you Stuart for sharing your story. If you've got a perspective on fatherhood you'd like to share, please get in touch. I'll see you all on Friday, unless you're a subscriber—in which case, you'll be getting another email later this week. Please follow The New Fatherhood on Twitter and Instagram. Send me links, comments, questions, and feedback. Or just reply to this email.

Branding by Selman Design. Illustrations by Tony Johnson (he'll be back next week.) Subscribe to support The New Fatherhood and join a private community of like-minded fathers all helping each other become the best dads we can be.

If you want a subscription, but truly can't afford it, reply to this email and you'll get one, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

This resonated so much with me, Stuart. Thank you for writing this piece.

My daughter Em turns three in a few days. She has severe cerebral palsy and is unable to walk. So most of the time when we're out and about she's in her custom stroller, which is basically a fancy wheelchair. Then add in the fact that we have to feed her through a tube with a giant syringe and you can see why we get stares all the damn time. It makes us feel like zoo animals or a trainwreck people can't take their eyes off of.

I totally get your wish to go back to being invisible. Trust me, as a pretty normal-looking white dude, I can relate. But I'd rather people come up to us and ask a thoughtful question about her disability instead of staring and diverting their eyes when we look their way. We've had some great conversations with people who have asked questions. It's not only less uncomfortable, but it's also an opportunity for people to learn more about a disability they might not know much about. This is also part of why I'm writing my family's story in public—to create a little bit more empathy in the world.

My only child, my son was born with severe deformed right leg and hand.

The right foot was short, small with only two toes and his palm had five fingers all fused together and half the size of his normal hand.

Eventually below the knee amputation was suggested for him. At the age of 13 he learnt to walk with the help of a prosthesis, before amputation also he needed a prosthesis but that was painful and was diagnosed that it would harm his hip bone and eventually he wouldn't be able to walk. So we went for amputation. Now it's all like normal. For his hand, the doctors said that since all the fingers were fused together and were missing individual bones nothing could be done. Luckily, one finger had all the bones, so they seperated it and created a thumb for him so he may ride a bike or handle a tool if he wanted so.

I still remeber when he was a kid. His first day at school. His walking with prosthesis, his non normal hand, were all enough for other kids to trigger me with questions.

Whenever I traveled with my kid I just couldn't bear the stares of fellow passengers and there questions. It always hurt me when I saw my son hiding his right hand in his pocket and shaking hands with his left hand.

But that was past. My son, now 21, has learnt to deal with all his difficulties and is in college. He has his own YouTube channel. Has many reel time and real time friends and he's among toppers in his academic career. Now he doesn't hide his hand, in fact he shakes hand with his right hand and answers all the questions with ease.

In short, he's capable of doing all that a normal kid can.