The Day I Let My Daughter Be Baptized

What happens when love and belief collide on a humid morning in the Philippines

This newsletter chronicles the stories of dads worldwide who attempt to navigate a version of fatherhood very different from the one they inherited. One of many diversions along the path is how we choose to raise our children in contact with religion, deciding which traditions to continue and which to abandon, as we attempt to make spirituality an invitation, not an obligation (a great line I picked up from a Dadscord dad).

One fellow wanderer on this journey is Jason Basa Nemec, a recovering academic who lives with his family in Chicago. He runs In Bar, a mobile craft cocktail business, and occasionally writes a Substack newsletter called Ideas Over Drinks.

Over to you, Jason.

The question had been eating at me for weeks: “Why are we doing this?”

I waited to ask my wife until we were on the plane from Hong Kong to the Philippines, where our child’s baptism was scheduled to take place. It was, I’ll admit, a little late to back out.

EJ was 20 months old. I watched as she kept putting her hand through the cup holder on the tray table and taking it back out again.

“Doing what?” asked Jenny. “Going to the Philippines, or getting her baptized?”

“Getting her baptized,” I said.

Jenny didn’t look at me. She was focused on EJ, tickling the little claw of her fingers from underneath the flip-down cup holder. EJ had started cracking up each time her and Jenny’s fingers touched, and as I smiled at this, a part of me regretted asking the question. The laughter of a child can do that to you, instantly putting any of the serious concerns you think you have on mute.

“We’ve already had this conversation.” Jenny’s tone was blunt but not without kindness. This is, perhaps, my wife in a nutshell: a whole lotta love, and yet no nonsense. No time for overthinking the past or holding on to worry. That’s me. I’ve always been the more anxious member of our partnership, and as the plane lifted off from the runway, I felt a deep uncertainty, curling into my gut like the unseen landing gear somewhere beneath me.

Two and a half hours later, we were in a cargo van, driving from the airport in Manila to Tito Rene’s house in Bulacan. My mother-in-law, whom we call Lola (the Tagalog word for grandmother), turned around to look at EJ. “When the priest touches you,” she said, “you will say amen.” Then she grabbed EJ’s hands, pressing them together as she repeated the word amen.

“Eh mon,” EJ finally said, pancaking her hands.

“Good!” said Lola. “A-men.”

“Eh mon.”

“Good enough,” said Lola.

She sounds Jamaican, I wanted to say. But I held my tongue, watching out the window as motorcycles and jeepneys sputtered through the congested streets. I had been to the Philippines twice before. The first time, in 2010, we brought the ashes of Jenny’s dad with us, all the way from Michigan. We locked the blue and white urn into an open-air tomb around the corner from a dirt yard that was hosting a cockfight. The younger cousins lit tea candles. Lola, who was technically not yet a Lola, thumbed a rosary while the other women in the family led us through Hail Mary after Hail Mary. Then, I dutifully mumbled the words, unable to shake the sense of doubt that bloomed in me after every phrase, fearful that my skepticism would somehow detract from the power of the prayer for the others, the believers who needed it more than me.

In the van, my wife reached forward and put her hand on EJ’s shoulder. “Why don’t you ask Lola to tell you what that means? Say, ‘What does Amen mean, Lola?’” This move by Jenny was either pro or manipulative, depending on who you ask: use the cute kid as a mouthpiece, instead of talking directly to an adult about a complicated subject. It’s a passive-aggressive move, sure, one I’ve used on my own parents, and even my own partner at times when I’m feeling annoyed and arguably petty, like when we’re sitting at dinner and I turn to EJ and say, “Can you ask Mama why she’s on her phone so much at the dinner table?”

Again, Lola pressed EJ’s hands together. “We pray, right?” Now she was the one speaking to/through our 1-year-old.

No one responded. The conversation died out then. At one point in the drive, Lola started to use EJ’s favorite stuffed animal, a giraffe named Peachy she sleeps with every night, to teach her how to make the sign of the cross.

Don’t, I thought, watching Lola move the little giraffe hoof up and down, then side to side. Don’t you dare turn Peachy into a priest.

I grew up Catholic. One of my earliest memories is of playing with a G.I. Joe figure during mass. He was a medic, clad in a red jumpsuit, white helmet, and aviator sunglasses. I would run him up and down the pew, in and out of the wooden hold of hymnals as the egg-shaped priest droned on and on. One day, as we exited the church, I remember my mom talking to the priest, saying, “Well, yes, he usually has to take a little toy along with him, but he’s quiet, he behaves himself.” This was the first time I noticed adults talking about me as if I wasn’t there. It struck me that what mattered most to these adults was not that I understood what I was doing in a place, but that I was quiet and behaved myself.

“We both come from two very Catholic families,” Jenny had reminded me on the plane. This is true, but we don’t go to church (except back in Ohio or Michigan on Christmas, with all the other out-of-town sinners). And we take issue with a number of the Catholic Church’s archaic stances, especially their refusal to allow women to become priests, along with their continued prohibition of marriage by same-sex couples. Why should we force our kid into a belief system we don’t fully believe in?

So, why are we doing this? Two days after our arrival in the Philippines, EJ was in the crook of my arm in her white baptismal dress, hi-fiving a life-sized cardboard cutout of Pope Francis, and I still didn’t have my answer. We were at the back of St. Michael’s Archangel church in Bulacan, trying to keep EJ occupied while we waited for the priest to show up. The air was humid and musty. Across from the cardboard Pope, a massive crucifix hung low on the wall. The wooden Jesus’s eyes were glazed with death. Mock blood dripped from the thick pins in his wrists.

I studied Postcolonial Literature in graduate school, which took my residual Catholic guilt and wound it into a thick, intellectual gauze of white guilt. Now, staring at the waxy, indie-rock bearded face of a guy who looked nothing like any of the brown-skinned members of my wife’s family scattered throughout the church, I wondered how, if at all, I was supposed to explain this contradiction to our kid. Why did Jesus look so different from all these people who worshipped him?

“So you see, EJ, hundreds of years ago, people sailed ships to the Philippines from a place called Spain, and brought their beliefs in this Jesus guy with them. They claimed they were being nice, but they really weren’t. They did a lot of taking. Then came people from America, which is where we’re from, and they did even more taking. And then the Japanese came, and then the Americans again, and then…”

Before I knew it, we were being ushered to the front of the church. The priest, a young Filipino guy with glasses, had arrived. He made small talk for a few minutes before beginning the ceremony. “Was I in the army?” he asked. “Was that the reason we were living in Hong Kong?” Like a lot of men I had met in Asia, he seemed almost painfully confused when I told him that my wife’s job, not mine, was the reason we had moved halfway across the world.

The ceremony was brief. When the priest poured water over EJ’s head, she sputtered and glared up at me as if to say “What the hell was that all about?!”

“You are a new creation,” the priest said. “You are an angel now.”

Come on, Father, I thought, watching as he thumbed the cross into EJ’s forehead. Don’t give me that rebirth rhetoric. Our kid was an angel from day one.

“And together we say, Amen.”

“Amen.” Lola said it loud and clear.

EJ, still stunned from the water, said nothing. Not even an “eh mon” escaped her little lips. I gave my wife a weak smile and she returned it. “Amen,” I said, my eyes on Jenny and not the priest. So be it.

Why did we do it? To appease our Catholic parents? That’s the obvious answer. And yet why did we need to appease them? Didn’t our parents already accept EJ? Of course they did; for evidence, one need look no further than the way their faces lit up anytime their grandchild so much as glanced in their direction.

“EJ can decide about church when she’s older,” Jenny said. “But if we didn’t get her baptized now, we’d be taking away her right to belong.” I understood what my wife was saying. I just didn’t fully agree with it. I find it fascinating that my wife and I can move forward in our lives together while not seeing eye to eye on big issues like this one. But isn’t that what faith is? An evolving belief in something—your partner, your God, your little kid who laughs gorgeously in some moments and screams like absolute hell in others—that just sort of pulls you along through your days, often makes no sense, and sometimes goes deathly silent.

Over seven years have passed since we walked out of that church and headed back to Tito Rene’s to stuff our faces with head-on fish and fresh mangoes. We have a second child now, Juniper, whom we did not baptize. As far as I’m concerned, the reason we didn’t do it for Juni is not because she’s prone to vicious meltdowns and has been known to strip her clothes off and spit on the floor when she’s mad, but because we no longer needed our parents’ blessing for how we choose to raise our kids. And if Juni grows up and decides she does want to get baptized in the Catholic church, she can sign up and have at it. I’m sure some pious (and brave) soul will happily splash holy water on her.

My wife, not surprisingly, sees it a little differently. Not long ago, when I asked Jenny why we went through with the baptism for EJ but not for Juni, she didn’t respond right away. She thought for a few seconds, then laughed and said something about how the second kid always gets forgotten about.

Is it that simple? Somebody’s god only knows.

3 things to read this week

“The Millennial Parent Trap” by Kate Mossman in The New Statesman. A wonderful essay that powerfully captures the work so many of us are doing, raising kids while breaking the mould at the same time. I could have shared ten highlights here, here’s just one: “My generation is trying to heal through raising children. Hot on therapy and faced with knowledge of our own, inner “wounded child”, we project our wounds on to our babies, and parent with an acute connection to what we were.”

“The Mistake Parents Make With Chores” by Christine Carrig in The Atlantic. As my kids are getting older, the topic of chores is becoming a regular talking point. In this essay, a Montessori teacher reflects on how well-meaning parents accidentally squash their kids’ desire to help by insisting on doing things “properly” themselves. Her insight, backed by developmental research, is simple but profound: kids’ clumsy early efforts help them learn competence, belonging, and care.

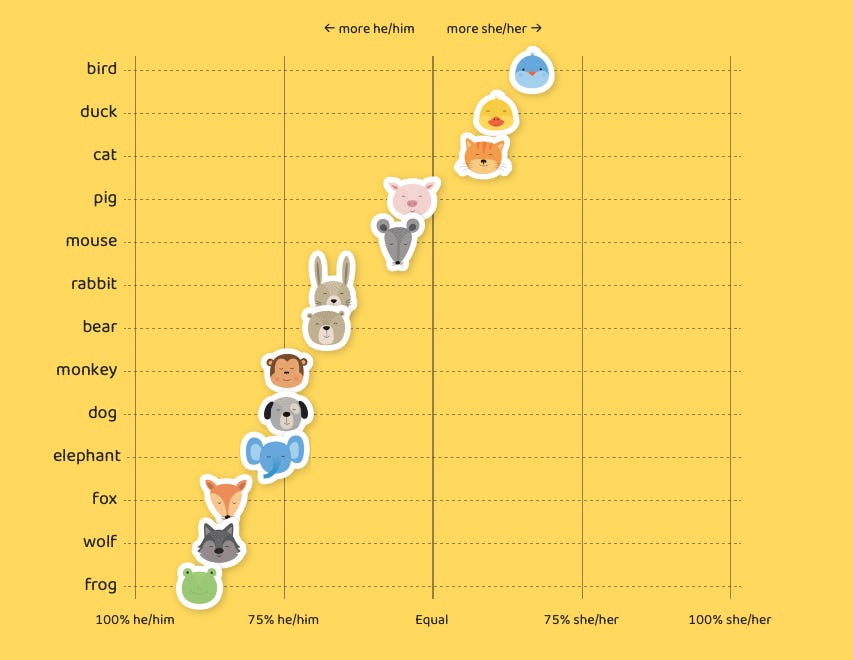

“Bears Will Be Boys” by Melanie Walsh in The Pudding. The Elephant and Piggie books by Mo Willems have always been a huge hit in our house, and continue to deliver great value as my son transforms from listener to reader. I Will Surprise My Friend, our current favourite, confirmed a suspicion I’d had for a while: Gerald (the elephant) is a boy, and Piggie (the pig) is a girl. It’s not just me who thinks this; this “data analysis of animal gender in children’s books” backs it up.

Good Dadvice

Say Hello

How did you like this week’s issue? Your feedback helps make this newsletter better. Loved | Great | OK | Meh | Bad

Become a paid member to help me pay dads like Jason for their writing.

Branding and illustration by Selman Design.

Thanks so much for giving me the space to share this story here, Kevin!

This post nicely captures the nuances and ambiguities that parents face when introducing religion to their kids. I have an eight month old daughter and we recently did an infant baptism/dedication for her in front of our church congregation. We want her to have some kind of spiritual formation and internalize what we believe are the positive aspects of Christianity, without making religion coercive. My wife grew up in a rigid evangelical environment where church was not optional, questions were not welcomed, and a fundamentalist interpretation of the Bible was assumed to be the only way of reading it. We intend to do things differently with our daughter. What does that look like? We’re still trying to figure that out.